Making advertising advertising-y

‘Art exists so that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.’

So wrote Viktor Shklovsky in his seminal Art as Technique (1917). So wrote I in my first ever Big Scary University Exams, referring to a poem about soup and relishing the opportunity to repeatedly describe things as ‘soupy’.

We understand this about art, instinctively. It makes us feel things. It makes us buy things.

It does this, says Shklovsky, by imparting sensation. Or, more accurately, it refreshes sensation because it tends to take the things we know – like stones – and makes us consider them in a new light. Art is a way out of what he calls the ‘habitual’, the humdrum everyday. It allows us to renegotiate perception by making objects unfamiliar, increasing ‘the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end itself and must be prolonged’.

In simple terms, the purpose of art objects according to Shklovsky is to jolt us out of the everyday environments to which we are accustomed.

The purpose of advertising according to everything we’ve learned this term, is to jolt us out of the everyday environments to which we are accustomed and then make us buy something.

That’s craft.

When we make the stone stoney, we essentially divorce sensation and context. It is easy to know what the image of a stone would feel like if it were a real stone. It is surprising to then be handed a stone and to discover that it is jelly-like, or that the thing which we thought was a stone was actually a clever hip flask, and we can buy one now for £25.50. We’re going to look at real stones different afterwards. But we also very much might make that purchase decision.

The work we do makes the stone stony, and then sells it.

The renegotiation of the familiar is in many ways advertising’s bread and butter. The work we do frequently comes straight from a kind of commericalised uncanny valley.

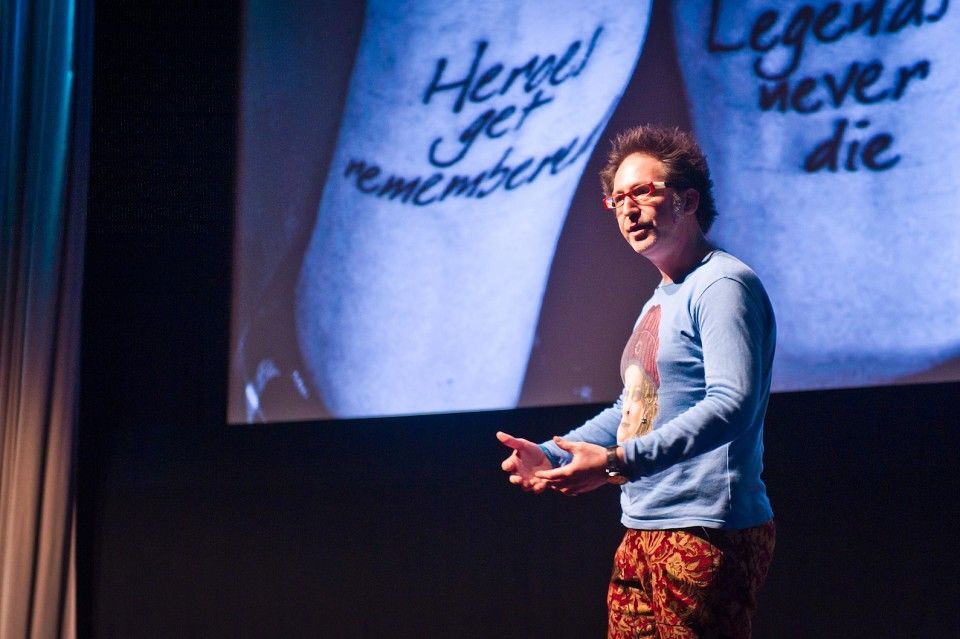

One of the techniques we are taught at school by the man, myth, and legend Gary Neill is to use what he calls ‘visual ingredients’ as a way into idea generation. Some things, Gary points out to us over a large sheet of paper, look like other things. They hold the same shape, or the same colours. But you can renegotiate them and make art, or as we say in the industry The Work or Hey That’s Got Legs Actually.

Look at Guinness ads. Lots of things look like Guinness, once you decide they do. A yellow post-it stuck to a crumpet looks like butter, points out Gary. Suddenly, we are unable to forget the Lurpak, even if we tried.

As a copywriter, this was what made me feel that I’d at least be able to get by in art direction. Things look like other things, I wrote down. That much I can manage.

Shklovsky, who likely was not an art director either, summed it up more eloquently than me or Gary have managed to so far when he said that art’s purpose is to ‘impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known’. But that’s because you can talk like that if you’re in 1917.

So advertising in many ways is selling sensation, a renewed sense of the feelings we have familiarly ignored about objects and concepts that are habitual in our lives.

Marc is particularly fond of the defamiliarisation of sliced bread as ‘edible plates’. You can see how here we take a familiar object and give it new life by making us think about it in a new way. The idea is at once a radical reconsideration of the nature of sliced bread and a great platform for selling. Marc would call it reframing, but he is essentially picking up what Shklovsky laid down back in the day.

What I take from all this is that regardless of how terrible your scamps look, when you create good advertising you are basically creating art, in the sense that your work should encourage its audience to reconsider the familiar. Like the famous Silk Cut ads, which use, among other vessels, a rhino in a hat to make silk silky (or cut cutty). Like Coca-Cola, which transcended the beverage category to sell a feeling. Like Honda, which became not just a car, but a dream (and a banana) thanks to savvy defamiliarisation.

And, yes, I think this is probably why we have such an affinity for Cadbury’s infamous gorilla. But maybe it’s just funny.