How I learned to stop worrying and always question the brief – By @MadDavison

By Mark Davison

How I learned to stop worrying and always question the brief

The great thing about creative work is that there are no right answers. There is no one answer that you get or you don’t. There are no perfect scores, no marks out of 10. There are only peoples’ opinions, some of which you will agree with, and some you will think make about as much sense as Donald Trump’s latest campaign speech. But while this means that you can always push boundaries and explore new ideas, it also means that sometimes people won’t like what you think is a great idea, just because.

So, in order to make sure our creative work is being objectively judged against something real, we need to make sure we have a rock solid brief. If our work is answering all the questions, and achieving all the objectives of the brief, then it’s much harder for someone to dismiss it, just because they don’t like the colour green.

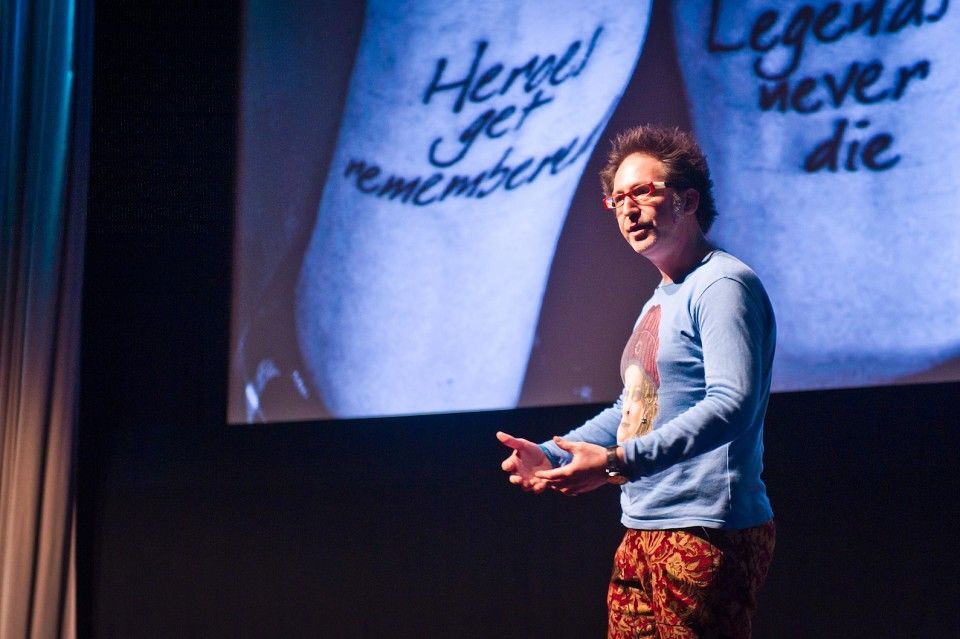

On Thursday we were lucky enough to have Patrick Collister (please come back

@directnewideas we love you) in to speak to us. One of the many topics he covered was questioning the brief, making it as clear and as limited to alternative interpretations as possible. The way to do this, he said, was through removing abstract and intellectual concepts.

Abstract and intellectual concepts are things such as love, hate, beauty, freedom, excitement, fun, or anything else that can be interpreted differently by two people. If we take, for example, fun, my idea of fun, watching Arsenal thrash Chelsea 3 nil at the Emirates a few weeks ago, might be very different to yours, particularly if you are unlucky enough to be a Chelsea fan.

So if we take that example and look at a brief, we could have something that says, “we want the user to have fun while watching this ad”. Now, I could take that to mean that we need to make them laugh, or that we need to get them emotionally engaged, or give them a mystery to solve, or…. you get the idea.

But if we are going to take these ideas out of our briefs, we need to replace them with something. After all we can’t have a brief without any descriptions in it at all, or it will be useless. Instead we need to replace them with concrete ideas. Instead of saying, “we want the user to connect emotionally” say, “we want to make people who watch it cry”. Instead of saying, “we want to speak to young people who are fun loving and out going” say, “we want to speak to people aged 20-35 who live for the weekend, who look forward all working week to being able to set loose with their mates on a Friday night at the latest bar or club they haven’t been to yet”.

So as Patrick told us, always question the brief, and make sure that you understand exactly what is meant by every word written, because otherwise your work probably isn’t going to answer the question that who ever wrote it meant to ask.